The Legality of MDMA in California

January 11, 2021

by Omar Figueroa

3,4-Methyl

In early 2020, the FDA authorized MDMA-assisted therapy for difficult-to-treat PTSD under another MAPS initiative pursuant to the FDA program known as Expanded Access. Expanded Access is a program that allows the use of an investigational drug under a Treatment Protocol for people facing a serious or life-threatening condition for whom currently available treatments have not worked, and who are unable to participate in Phase 3 Clinical Trials.

Looking at the larger picture, MAPS’ stated goal is to develop MDMA-assisted therapy for PTSD into an FDA-approved prescription treatment.

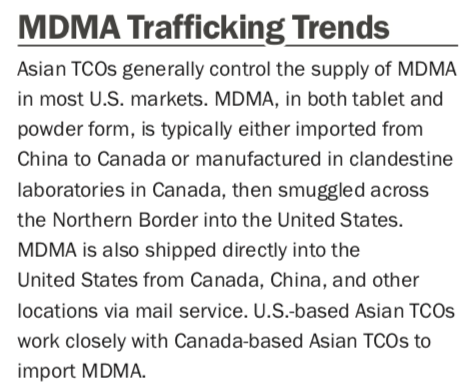

While promising medical research continues, the market for illegal MDMA remains significant. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration’s 2019 National Drug Threat Assessment, “Asian TCOs [Transnational Criminal Organizations] also remain the primary 3,4-Methyl

These disturbing race-based categorizations are echoed in the federal “Drug Market Analysis 2011” prepared by the Northern California High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area:

Translation: “The availability and abuse of Other Dangerous Drugs, principally MDMA, vary throughout the Northern California High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area region — MDMA availability and abuse remain stable at high levels in most areas. Canadian-based Asian Drug Trafficking Organizations smuggle most of the MDMA available in the region from Canada through Washington Points of Entry and into the region. […]” Although this report is a decade old (it’s the most recent version we could find, as generally this type of information is restricted), these antiquated conclusions are similar to the more recent conclusions presented in the 2019 National Drug Threat Assessment.

At the state level, there are several questions: how illegal is MDMA under California law? Is there a viable medical defense? What about a religious defense?

Surprisingly, MDMA is not expressly prohibited under California law. Although “3,4-methylenedioxy amphetamine” (MDA) is listed as a Schedule I controlled substance at Section 11054(d)(6), MDMA is not on the list of controlled substances enumerated in California’s Uniform Controlled Substances Act.

In 2013, the California Supreme Court reversed convictions for sale and possession of MDMA for insufficient proof. People v. Davis (2013) 57 Cal.4th 353. Reasoning that the California Health and Safety Code does not list 3,4-Methyl

In sum, the California Supreme Court held that while MDMA is not expressly prohibited, a jury may find MDMA is a controlled substance or analog based either on evidence of MDMA’s chemical composition (either containing a controlled substance or having a substantially similar chemical structure) or its purported effects on the user. Turning to the facts before it, the Davis Court held that evidence of MDMA’s chemical name, standing alone, was insufficient to prove that MDMA contains a controlled substance or meets the definition of an analog. It was incumbent on the prosecution to introduce competent evidence about MDMA’s chemical structure or effects, and without such evidence, there was no rational basis for a jury of laypersons to infer that 3,4-methyl

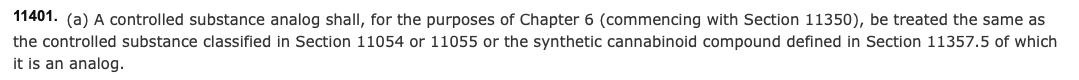

Under the analog statute, Health & Safety Code § 11401(a), a controlled substance analog is punished the same as the controlled substance of which it is an analog.

For example, an analog of methamphetamine is treated the same as methamphetamine, an analog of amphetamine is treated the same as amphetamine, and an analog of MDA is treated the same as MDA.

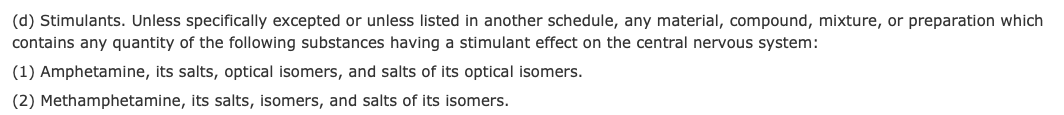

Under California law, amphetamine and methamphetamine are classified as a Schedule II stimulants at subdivisions (d)(1) and (d)(2) of Section 11055 of the Health & Safety Code:

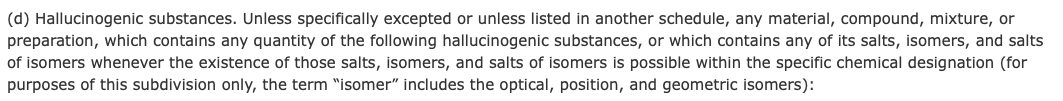

MDA is classified as a Schedule I hallucinogenic substance at subdivision (d)(6) of Section 11054 of the Health and Safety Code:

Unlawful possession of any of these substances is forbidden by Health and Safety Code Section 11377 , which ordinarily is classified as a misdemeanor punishable by up to one year in the county jail unless the person has certain aggravating “priors.”

Pursuant to Proposition 36, anyone charged with personal use, possession for personal use, or transportation for personal use of such controlled substance (amphetamine, methamphetamine, MDA, or their analogs), may qualify for drug treatment instead of jail. The court must grant probation as an alternative to incarceration to qualifying defendants convicted of “nonviolent drug possession offenses,” as defined in Penal Code § 1210(a). Penal Code § 1210.1(a). Courts must impose, as a condition of probation, completion of a drug treatment program not to exceed 12 months, with optional aftercare of up to six months. The court may also require that the defendant participate in vocational training, family counseling, literacy training, and/or community service. Penal Code § 1210.1(a). Qualifying defendants must consent to participate in a drug treatment program, must be amenable to treatment, and must not otherwise be excluded from participation under Penal Code § 1210.1(b).

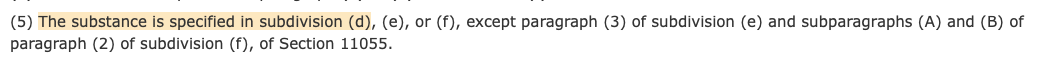

The scope of Proposition 36 is narrow and does not apply to sales-related offenses. For example, Health and Safety Code Section 11378 forbids the possession for sale of any “material, compound, mixture, or preparation” containing MDA, amphetamine, or methamphetamine or their analogs. The crime is classified as a non-reducible felony subject to sentencing pursuant to Penal Code Section 1170(h), which generally means up to three years in the county jail.

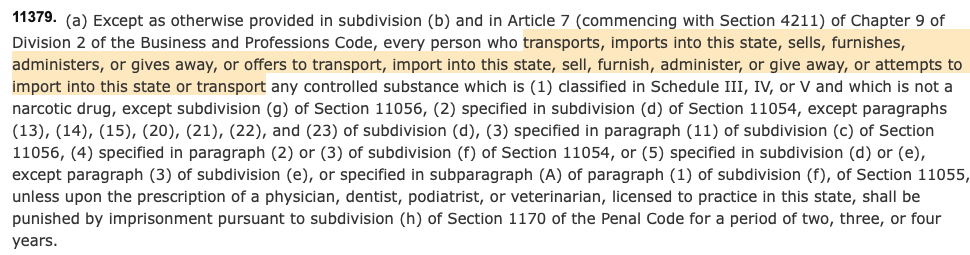

Moreover, Health and Safety Code Section 11379 forbids numerous activities as felonies which are generally punishable by up to four years in the county jail. Thus, anyone who “transports, imports into this state, sells, furnishes, administers, or gives away, or offers to transport, import into this state, sell, furnish, administer, or give away, or attempts to import into this state or transport” certain specified controlled substances (including any “material, compound, mixture, or preparation” containing MDA, amphetamine, or methamphetamine, or their analogs) faces substantial criminal exposure for conduct which constitutes a non-reducible felony under California law.

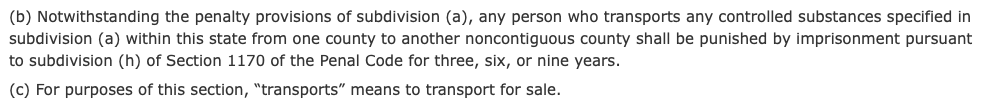

Additionally, subdivision (b) increases the criminal exposure to nine years for any person who transports controlled substances “within this state from one county to another noncontiguous county.”

This means, for example, that if a person were to transport for sale from one county to another any “material, compound, mixture, or preparation” containing MDA or amphetamine, or methamphetamine (or their analogs), and the counties are contiguous (meaning adjacent), the criminal exposure is a maximum of four years; however, if the counties are not contiguous (meaning the person travels through a total of three or more counties) the criminal exposure increases to a maximum of nine years in the county jail.

This means, for example, that if a person were to transport for sale from one county to another any “material, compound, mixture, or preparation” containing MDA or amphetamine, or methamphetamine (or their analogs), and the counties are contiguous (meaning adjacent), the criminal exposure is a maximum of four years; however, if the counties are not contiguous (meaning the person travels through a total of three or more counties) the criminal exposure increases to a maximum of nine years in the county jail.

The case law interpreting Health and Safety Code Section 11379 is draconian. For example, in People v. Patterson (1999) 72 Cal.App.4th 438, the Third Appellate District of the California Court of Appeal held that, in order to prove the offense of transportation of a controlled substance for sale between noncontiguous counties, the prosecution did not have to prove that defendant intended to facilitate the sale of the drug in the noncontiguous county. The Court of Appeal rejected the defendant’s construction of the statute, which would “place an onerous burden upon law enforcement to identify the county in which a defendant who is transporting illegal drugs intends to sell them.” 72 Cal.App.4th at 445.

Let us consider the following thought experiment. A person travels by car from San Francisco to Palo Alto to sell (at cost) a few dozen tablets containing MDMA. The vehicle is pulled over for speeding on 280 near Page Mill. The driver is nervous, and the officer starts asking lots of questions. The person panics and blurts a confession: they were transporting MDMA from San Francisco to Palo Alto to sell at cost. The person is arrested; the MDMA is seized and sent to the crime lab for analysis. According to the crime lab, the suspected MDMA is not 100% pure; it contains a bit of methamphetamine too, which makes the prosecution’s case easier to prove.

Because the City and County of San Francisco is not contiguous with the County of Santa Clara (one has to travel through either San Mateo County or Alameda County), such transportation for sale would constitute a non-reducible felony punishable by three, six, or nine years in the county jail, depending on the circumstances. It makes no difference that the person intended to sell the MDMA at cost; the law does not require that the seller intend to make a profit, only that the seller intend to make a sale.

Could there be a viable medical defense outside of clinical treatment by medical professionals? Possibly, if one can establish medical necessity by showing that the person has no adequate alternatives to the charged conduct. Realistically, depending on the circumstances, it would be an uphill battle given that criminal courts tend to be skeptical of the medical necessity defense. For example, in People v. Trippett (1997) 56 Cal.App.4th 1532, the California Court of Appeal affirmed the trial court’s rejection of the medical cannabis necessity jury instruction requested by legendary activist Pebbles Trippet, reasoning that she was not entitled to a necessity defense because she failed to establish that she had no adequate alternatives as she could have taken prescription Marinol instead of transporting pounds of cannabis as alleged. On the other hand, one can imagine a situation where a Court would allow a medical necessity defense for a veteran who is self-medicating with MDMA for PTSD after exhausting all other treatment options, as long as the circumstances show that the MDMA is intended solely for personal medical use.

What about a religious defense? As one can also read in the Trippett decision, criminal courts tend to be skeptical of the religious defense and treat such claims dismissively. Absent express statutory protections, a religious defense based on the First Amendment is not viable given United States Supreme Court precedent such as Employment Division v. Smith, which held that the First Amendment does not require states to accommodate illegal acts performed in pursuit of religious beliefs, and City of Boerne v. Flores, which struck down the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act as it applies to the states as an unconstitutional use of Congress’s enforcement powers.

A different approach would be to rely on the Free Exercise Clause of the California Constitution, which provides, in pertinent part:

Free exercise and enjoyment of religion without discrimination of preference are guaranteed. This liberty of conscience does not excuse acts that are licentious or inconsistent with the peace and safety of the State. The Legislature shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.

California Constitution, Article I, section 4.

The Assembly Judiciary Committee of the California State Legislature has authored an extensive Background Paper summarizing California’s Free Exercise Clause case law, and distilling arguments concerning a proposal, Assembly Bill 1617, to augment existing protections via a California version of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. As the Background Paper notes, there is considerable ambiguity about the level of judicial scrutiny afforded by the Free Exercise Clause of the California Constitution. The California Supreme Court has declined to decide the question of whether the compelling interest test applies when the Free Exercise Clause of the California Constitution is invoked, leaving open for a future day the question of the scope of state constitutional protections for the religious use of MDMA.

In sum, MDMA is not expressly forbidden under the California Uniform Controlled Substances Act, but can nevertheless be prosecuted as an analog of scheduled controlled substances such as MDA, amphetamine, or methamphetamine, or, if it’s “dirty” and contains a scheduled controlled substance, as that scheduled controlled substance.

The time has come to update the legal landscape pertaining to MDMA in California, and we look forward to future legislation that not only respects the mental autonomy of individuals but also advances cognitive liberty.

This information is provided as a public educational service and is not intended as legal advice. For specific questions regarding psychedelics law in California, please contact the Law Offices of Omar Figueroa at 707-829-0215 or info@omarfigueroa.com to schedule a confidential legal consultation.