The Legality of LSD in California

January 14, 2021

by Omar Figueroa

California has been at the forefront of psychedelic policy change for years. In 2019, the City of Oakland became “the first in the nation to decriminalize a wide range of psychedelics such as psilocybin mushrooms and ayahuasca.” More recently, on November 15, 2020, State Senator Scott Wiener tweeted, “It’s time to take a health/science based approach to drugs & move away from knee-jerk criminalization. Psychedelics have medicinal benefits & they shouldn’t be illegal. That’s why, when the Legislature reconvenes, we’ll work to decriminalize their use.”

Senator Wiener’s tweet linked to a news article which discusses increasing numbers of patients and therapists coming out of the psychedelic closet. According to the article, Senator Weiner “said he was leaning toward Oregon’s supervised-use approach while allowing for the use of synthetic psychedelics such as LSD.”

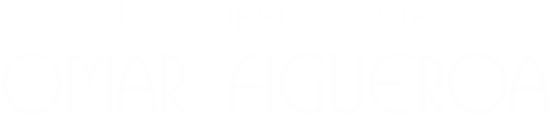

LSD has been the focus of research since its discovery by Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann in the Sandoz (now Novartis) laboratories in Basel, Switzerland, on Bicycle Day, April 19, 1943. LSD has played a role in the 21st century resurgence of psychedelic therapy, but there are only a handful of modern studies. These studies are discussed in the article Modern Clinical Research on LSD published in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology in 2017, which noted that, in “medical settings, no complications of LSD administration were observed” and concluded that such “data should contribute to further investigations of the therapeutic potential of LSD in psychiatry.

At the federal level, LSD-related activities are subject to draconian penalties. For example, the United State Supreme Court held in Chapman v. United States that the weight of the blotter paper containing LSD, and not the weight of the pure LSD itself, is what triggers the mandatory minimum. Since there is a five year mandatory minimum under federal law for more than one gram of blotter paper containing LSD, and a sheet of paper weighs approximately 4.5 grams, less than a quarter of a page of blotter paper containing LSD would hypothetically trigger the five year mandatory minimum, even if the total weight of the pure LSD in the blotter paper is no more than a tiny fraction of a gram. Similarly, there is a ten year mandatory minimum under federal law for more than ten grams of carrier medium containing LSD, so three sugar cubes (each weighing approximately 4 grams) with one dose in each sugar cube would weigh a total of twelve grams. In other words, three sugar cubes containing a total of three doses of LSD could trigger a potential ten year mandatory minimum sentence.

The question remains: how illegal is LSD under California law? Is there a viable medical defense? What about a religious defense?

Under California law, LSD is classified as a Schedule I hallucinogenic controlled substance.

California Health & Safety Code Section 11054, subdivision (d)(12). There is no medical or

exception in the statutes.

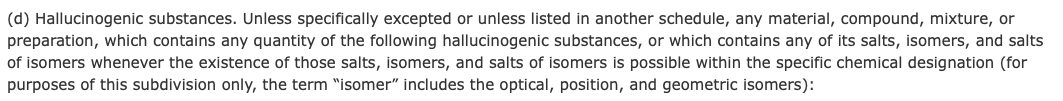

Because LSD is classified as a Schedule I hallucinogenic controlled substance pursuant to Health and Safety Code Section 11054, subdivision (d)(12), any “material, compound, mixture, or preparation” containing LSD is subject to prosecution pursuant to California’s Uniform Controlled Substances Act.

In particular, Health and Safety Code Section 11377 forbids the possession of any “material, compound, mixture, or preparation” containing LSD, which ordinarily is classified as a misdemeanor punishable by up to one year in the county jail unless the person has certain aggravating “priors.”

Pursuant to Proposition 36, anyone charged with personal use, possession for personal use, or transportation for personal use of a controlled substance, may qualify for drug treatment instead of jail. The court must grant probation as an alternative to incarceration to qualifying defendants convicted of “nonviolent drug possession offenses,” as defined in Penal Code § 1210(a). Penal Code § 1210.1(a). Courts must impose, as a condition of probation, completion of a drug treatment program not to exceed 12 months, with optional aftercare of up to six months. The court may also require that the defendant participate in vocational training, family counseling, literacy training, and/or community service. Penal Code § 1210.1(a). Qualifying defendants must consent to participate in a drug treatment program, must be amenable to treatment, and must not otherwise be excluded from participation under Penal Code § 1210.1(b).

The scope of Proposition 36 is narrow and does not apply to sales-related offenses. For example, Health and Safety Code Section 11378 forbids the possession for sale of any “material, compound, mixture, or preparation” containing LSD, which again is expressly classified as a Schedule I hallucinogenic controlled substance at Section 11054, subdivision (d)(12).

The crime of possession for sale of LSD is classified as a non-reducible felony subject to sentencing pursuant to Penal Code Section 1170(h), which generally means up to three years in the county jail.

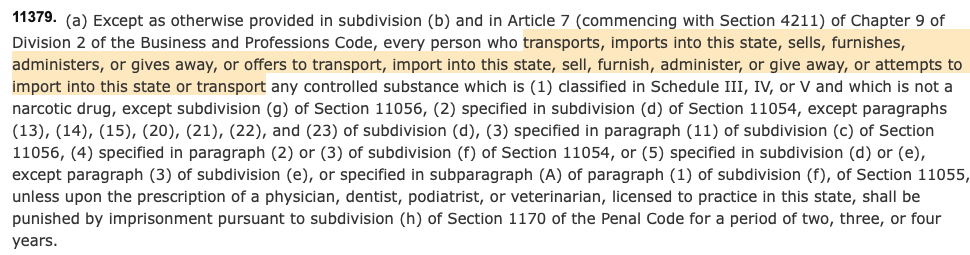

Moreover, Health and Safety Code Section 11379 forbids numerous activities as felonies which are generally punishable by up to four years in the county jail. Thus, anyone who “transports, imports into this state, sells, furnishes, administers, or gives away, or offers to transport, import into this state, sell, furnish, administer, or give away, or attempts to import into this state or transport” certain specified controlled substances (including any “material, compound, mixture, or preparation” containing LSD) faces substantial criminal exposure for conduct which constitutes a non-reducible felony under California law.

Additionally, subdivision (b) increases the criminal exposure to nine years for any person who transports controlled substances “within this state from one county to another noncontiguous county.”

This means, for example, that if a person were to transport for sale from one county to another any “material, compound, mixture, or preparation” containing LSD, and the counties are contiguous (meaning adjacent), the criminal exposure is a maximum of four years; however, if the counties are not contiguous (meaning the person travels through a total of three or more counties) the criminal exposure increases to a maximum of nine years in the county jail.

This means, for example, that if a person were to transport for sale from one county to another any “material, compound, mixture, or preparation” containing LSD, and the counties are contiguous (meaning adjacent), the criminal exposure is a maximum of four years; however, if the counties are not contiguous (meaning the person travels through a total of three or more counties) the criminal exposure increases to a maximum of nine years in the county jail.

The case law interpreting Health and Safety Code Section 11379 is draconian. For example, in People v. Patterson (1999) 72 Cal.App.4th 438, the Third Appellate District of the California Court of Appeal held that, in order to prove the offense of transportation of a controlled substance for sale between noncontiguous counties, the prosecution did not have to prove that defendant intended to facilitate the sale of the drug in the noncontiguous county. The Court of Appeal rejected the defendant’s construction of the statute, which would “place an onerous burden upon law enforcement to identify the county in which a defendant who is transporting illegal drugs intends to sell them.” 72 Cal.App.4th at 445.

Let us consider the following thought experiment. A person travels by car from San Francisco to Saratoga to sell one sheet of LSD. The vehicle is pulled over for speeding on 280 near Mountain View. The driver is nervous, and the officer starts asking lots of questions. The person panics and blurts a confession: they were transporting LSD from San Francisco to Saratoga to sell at cost.

Because the City and County of San Francisco is not contiguous with the County of Santa Clara (one has to travel through either San Mateo County or Alameda County), such transportation for sale would constitute a non-reducible felony punishable by three, six, or nine years in the county jail, depending on the circumstances. It makes no difference that the person intended to sell the chocolates at cost; the law does not require that the seller intend to make a profit, only that the seller intend to make a sale.

Could there be a viable medical defense? Possibly, if one can establish medical necessity by showing that the person has no adequate alternatives to the charged conduct. Realistically, it would be an uphill battle given that criminal courts tend to be skeptical of the medical necessity defense. For example, in People v. Trippett (1997) 56 Cal.App.4th 1532, the California Court of Appeal affirmed the trial court’s rejection of the medical necessity jury instruction requested by legendary activist Pebbles Trippet, reasoning that she was not entitled to a medical cannabis necessity defense because she failed to establish that she had no adequate alternatives as she could have taken prescription Marinol instead.

What about a religious defense? As one can also read in the Trippett decision, criminal courts tend to be skeptical of the religious defense and treat such claims dismissively. Absent express statutory protections for religious use of LSD, the religious defense is challenging given United States Supreme Court precedent such as Employment Division v. Smith, which held that the First Amendment does not require states to accommodate illegal acts performed in pursuit of religious beliefs, and City of Boerne v. Flores, which struck down the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act as it applies to the states as an unconstitutional use of Congress’s enforcement powers.

A different approach would be to rely on the Free Exercise Clause of the California Constitution, which provides, in pertinent part:

Free exercise and enjoyment of religion without discrimination of preference are guaranteed. This liberty of conscience does not excuse acts that are licentious or inconsistent with the peace and safety of the State. The Legislature shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.

California Constitution, Article I, section 4.

The Assembly Judiciary Committee of the California State Legislature has authored an extensive Background Paper summarizing California’s Free Exercise Clause case law, and distilling arguments concerning a proposal, Assembly Bill 1617, to augment existing protections via a California version of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. As the Background Paper notes, there is considerable ambiguity about the level of judicial scrutiny afforded by the Free Exercise Clause of the California Constitution. The California Supreme Court has declined to decide the question of whether the compelling interest test applies when the Free Exercise Clause of the California Constitution is invoked, leaving open for a future day the question of the scope of state constitutional protections for the religious use of LSD.

In sum, the time has come to update the legal landscape pertaining to LSD in California, and we thank legislators such as State Senator Wiener for envisioning a better future. Hopefully, 2021 will be the year when exciting legislative proposals begin long-awaited changes in the laws that govern our relationship with psychedelics such as LSD.

Example of psychedelic art on a perforated sheet of paper with stylized depiction of Albert Einstein.

This information is provided as a public educational service and is not intended as legal advice. For specific questions regarding psychedelics law in California, please contact the Law Offices of Omar Figueroa at 707-829-0215 or info@omarfigueroa.com to schedule a confidential legal consultation.